Trust and management

In this post I explore the importance of trust within a company, how it works, and some common managerial failures. I talk about software companies but I believe the same concepts apply to any business that does intellectual work, which in today’s world is most companies.

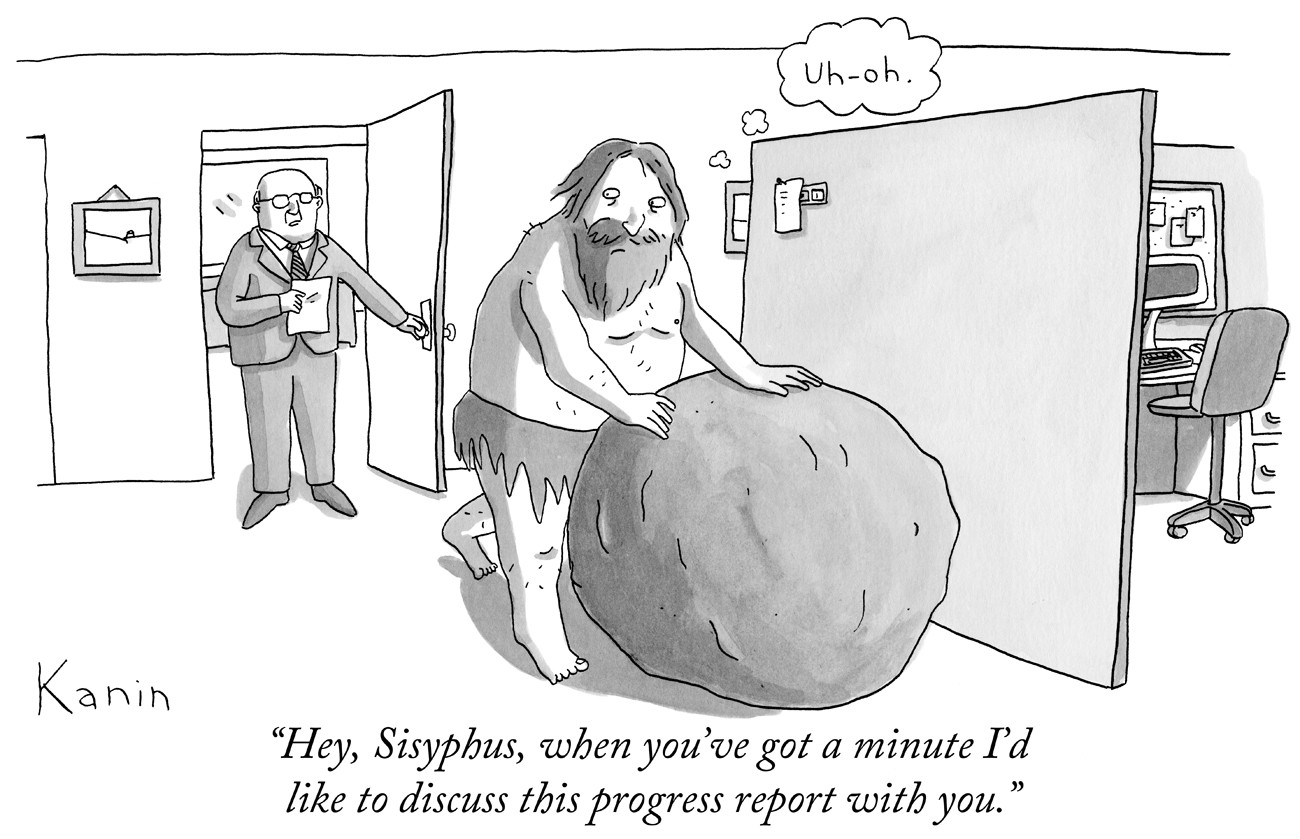

I’ve been thinking for some time about the systematic failures of management practices, especially in software companies. Evidence of this is so plentiful that there are entire comic strips dedicated to the topic.

I’ll start with the Wikipedia definition of trust (paraphrasing): “Trust is the willingness of one agent (trustor) to give over control to another agent (trustee) with the belief that some desired effect will happen in the future”. Keep in mind that this is my starting point — even if we disagree on this definition, it’s important (for me) that the rest of the text is consistent with this definition.

A few points are worth noting here:

- There exists a mutually desired future outcome (a goal) and an agreement to attain that goal.

- Trust involves giving away control. This means that the trustor has some kind of control over the future, which he is willing to let go of.

- Trust is something which is granted willingly. If we have no other choice but to trust someone, we don’t really have control over the situation either, so we’re not talking about trust.

- We don’t trust strangers. Trust implies that we know the trustee. There is another name for blind trust: faith.

Since trust involves giving away the “power of control”, it puts the trustor in a vulnerable position. It’s understandable, then, that people are not always happy with trusting others. You’ve probably heard the saying: “If you really want something done, do it yourself” — I certainly believe this. We generally don’t trust others because of two reasons: Either we don’t trust they can do what’s agreed, or we don’t trust they will do what’s agreed. We will call the first group of trustees “incompetent” and the second one “demotivated”.

If we believe the trustee to be competent and motivated, we can put our trust in them and enter into an “agreement” to achieve the desired goal. Reality, however, is uncertain and goals are almost never fully achieved. Let’s call these situations failures. There are three kinds of failures:

- Failure of communication: both parties did not understand the same goal.

- Failure due to inherent risk: something out of our control happened.

- Failure of misplaced trust: the trustee was incompetent or demotivated.

When trust can not be fully established, the only other option is to retain control. But controlling people is expensive and, I’ll argue, rarely needed. The only control people truly need to exert is the one over themselves.

This essay talks about how the handling of failures and wielding of control makes or breaks the trust in a company.

The importance of trust

The development of civilization and human society was shaped to a large extent by the invention of institutions that establish trust between strangers, or, at least, make it expensive for trust to be broken. In the last decade we have been obsessing with technological solutions for achieving trust-less consensuses. Trust is necessary to conduct basic human cooperation.

The “company” is one of those institutions that facilitate human cooperation. It’s is a mini society that gets to pick its members and set objective goals for them — something that wider societies can not do as easily. Precisely these mechanisms allow companies to leverage trust in order to efficiently cooperate.

Depending on the size and industry, between 0% and 99% of what a company does is not directly connected to achieving its goals but exists as a form of risk management or a vestige from an outdated process. Risk management is inherently connected to trust. We don’t trust who we don’t know, so we need to make sure they behave predictably. Companies establish various internal processes to manage these risks. As technology and culture evolves, these processes get outdated, sometimes to the point where they actively worsen what they were intended to improve. Maintaining processes requires time and effort which a company is not always willing to spend. Trust improves this situation in two ways: it reduces the need for risk management, but it also mitigates the effects of existing bureaucracy — you trust people to “do the right thing” despite what the rules say.

Autonomy is crucial for maintaining productivity while growing an organization hierarchy. Highly centralized (non-autonomous) organizations are effective but not efficient because they present decision making and communication bottlenecks. There is ample research evidence for this. Autonomy is inherently based on trust because it assumes that its elements operate with the same incentives.

One of the reasons small teams are more efficient than large ones is that small teams establish trust between its members more easily and reap the benefits from increased autonomy and decreased bureaucracy.

Apart from these “global” effects, trust also has very powerful effects at the individual level.

Trust and implicit messages

As humans, we understand situations at different levels, but we often use the word “understand” to describe the articulated level of understanding — when we can clearly explain why. You’ve probably heard the misattributed Einstein quote “You don’t really understand it if you can’t explain it to a six year old”.

But humans also understand things at an emotional level. Don’t beat me up over my usage of the term “emotional” too much — the point I’m making is that people often say “I feel this to be true” or they have “gut feelings” and “intuition”. I believe that we are able to hoist these feelings to the articulate level and talk about them rationally. This requires a lot of thinking, introspection and sometimes courage to face what you say out loud. This is what psychotherapists do, by the way. They help people utter what they already know so they can face it.

We understand everyday events at both articulate and emotional level. I’ll call the latter “the implicit message”. Let’s have a look at the implicit messages of trust and mistrust.

A person that is not trusted receives the following implicit message: “I don’t know you”, “you’re not competent”, “you’re not willing” or any combination of the three. People react differently to this. Some will be able to articulate the implicit message, others might get overtly hostile, or they might start feeding their insecurities. It’s hard work to articulate these emotions; it requires practice and skill and it’s not in anyone’s job description.

On the other end, what often happens in reality is that people are forced to pretend they trust others. There are many causes for this: nepotism, cronyism, overly zealous HR departments, to name a few. In these situations the trustor is forced to give control over to pure luck, and often to certain failure. You can imagine the kinds of emotions this stirs.

But when trust functions properly, everything is great. I’m sure you’ve had at least one coworker that you completely trusted: they were competent, and they would never fail you. Working with such people is pure bliss: Things just get done, mistakes are never scary, new ideas flourish, mountains are being moved and you become friends.

There is an underlying pragmatic reason for this. People you completely trust are like extensions of yourself, except they think differently and give you new ideas. When you stop wasting energy on protecting yourself from other people’s malice and incompetence, life becomes smooth sailing.

Trust creates a healthy and efficient work environment. Next we take a look at how companies systematically ruin that.

Mishandling failures

A failure happens when we put our trust in someone and they fail to uphold their end of the bargain. Failures are quite common. In fact, they are the norm. No project has ever been delivered on time, on budget and with the highest quality because that is impossible. That’s why every trust agreement has an implicit tolerance level that determines how far the achieved goal can stray from the ideal before we really call it a failure.

Failures of communication

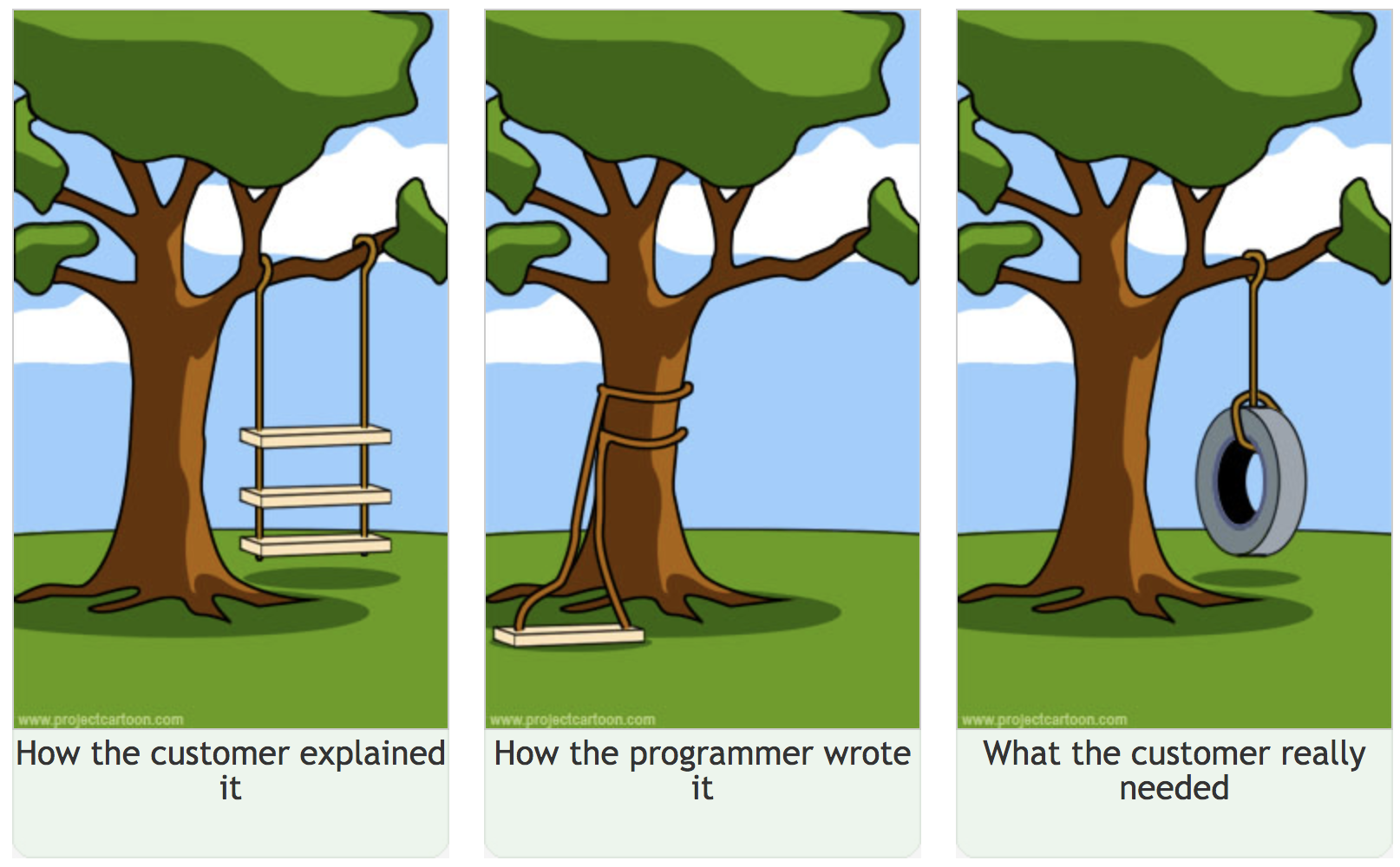

These are by far the most common kind of failure. They are so ubiquitous that there’s an entire meme culture around it.

There’s even a website for this: projectcartoon.com

There’s even a website for this: projectcartoon.com

Failure of communication happens when both parties did not have the same understanding of what needs to be done in the first place. This is not technically a breach of trust since both parties acted sincerely. However, the classical mistake is to misinterpret it like a failure of misplaced trust. Even though the fault is equally shared between both parties, people are still naturally inclined to blame the other.

Companies systematically repeat this mistake by punishing the trustee for failures of communication. This happens because it’s usually the manager who is also the trustor and has the power to punish. Mistakes like this lead to an ever growing mistrust in the employees and they are left with no ability to improve the situation.

The correct solution to this problem is, of course, to fix the communication. But it is also important to strip the power to punish from the manager so that future mistakes are less costly. This might seem like a radical move, but systematic failures of miscommunication are ultimately management’s fault.

Failures due to inherent risk

This is when things turn out to be different than what was originally expected. The same tendency to interpret these as failures of misplaced trust exist here as well. The damage done when this happens is more severe since it’s obvious to the trustee that “it’s not their fault”. This leads to even more frustration.

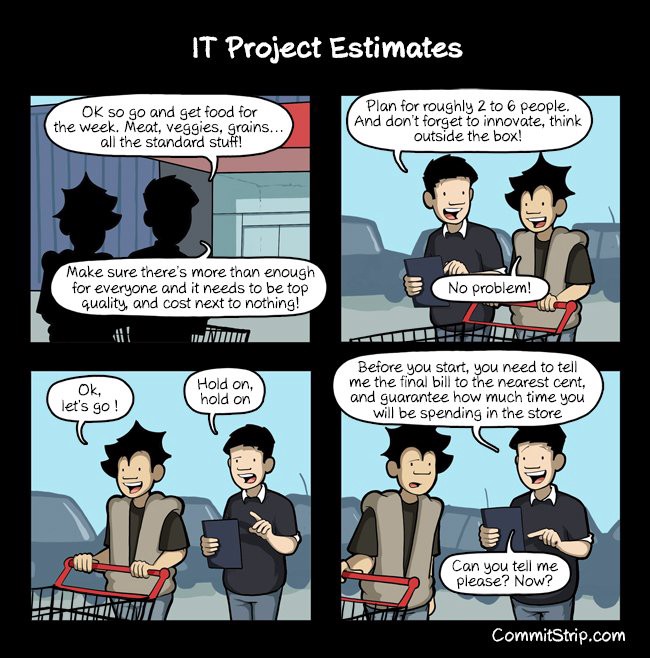

The real systematic mistake companies make, though, is not managing risk properly. The following comic is a good example.

Pretending we have more information than there really exists.

Pretending we have more information than there really exists.

It might not be obvious, but pretending to have “more correct” estimates than realistically possible and planning your future according to that is really just bad risk management. But this is a topic for another blog post.

When risk is properly managed we shouldn’t consider these failures to be failures at all. Either everyone expected that this might happen or nobody did. In any case there is nobody to blame so trust is not broken.

Failures of misplaced trust

These are the failures that get called out the most. To remind you — this is when the trustee was indeed trusted, but they failed to deliver either because of incompetence or lack of motivation.

These actually never happen in a healthy company. By definition we don’t place trust in people that we know are incompetent or demotivated. We certainly expect them to do things, but:

- If they are incompetent (e.g. they are learning), the failure is due to inherent risk.

- If they are “strangers”, and blind trust was put in them, the failure is also due to improper risk management.

- If they are demotivated, the company is not healthy.

It’s also worth mentioning a pathological variant of this failure: When the trustee deliberately fails. This is indeed a pathological case because it signals that something’s really wrong with the company. An example of this is going on a strike.

It’s worth noting that no company is 100% healthy.

Control

“Control” is what fills the void left by the absence of trust. It’s another way to get things done, but it’s the very antithesis of trust.

Control is needed, though, when trust is impossible to establish. For example, hiring people is controlling which stranger gets to join the company and firing people is controlling who gets to leave for not being trustworthy.

But control is deeply ingrained in today’s management practices. The company hierarchy often becomes synonymous with control instead of work delegation. People love control and for good reasons:

- Control is associated with power and people just love power very much.

- Having control gives people the option not to trust. Trust is hard work and makes us vulnerable.

But being the opposite of trust, control erodes it and should only be used insofar people understand and accept why they are not being trusted.

So let’s see how control erodes trust in companies. We’ll start with the worst offenders and move towards the more subtle ones.

Micromanagement

Micromanagement is an overt form of mistrust, where “I trust you so little that I basically need to get the job done myself. You are a dumb apparatus.”

Because micromanagement is such a vulgar display of mistrust, it’s no wonder people universally hate it.

The carrot and the stick

This is a very common motivational practice. It communicates that “I trust your competence, but I question your motivation”. However, motivation often stems from trust, so this method of control can have an even deeper trust-eroding effect. I’ve certainly heard the following sentence several times in my life: “He can take his bonus and shove it up his ass”.

Carrots don’t work because people are seldom motivated by the direct reward unless they badly need it. This begs the question if people are treated well or paid enough.

When money’s not the question, carrots can help when the motivation is power (status). This begs the question whether right kind of people are being rewarded. In a healthy company benefits from promotions should be cancelled out by the increased responsibility and workload. Everyone should be paid enough, and nobody too much.

Sticks don’t work either. I explain this in the failures section.

Ass in chair policies

This is controlling how much time employees spend at their desk. This method only gives you the illusion of control. Demotivated employees can slack on their desk just as well as away from it.

Sometimes companies think that blocking websites that people use to slack off will have an effect, but this degrades trust even further because it sends the same implicit message to the motivated as well.

Scientific management

Another way that companies erode trust is by enforcing processes whose sole purpose is to control. This is known colloquially as “corporate bullshit”. Some companies are so in love with process making that they culminate in turning the employee into a “cog of a well oiled machine”, effectively messaging: “I trust you to rotate, interlock your teeth with the other cog and nothing else”.

People however, are really good at sniffing out corporate bullshit at an emotional level. If you need evidence, spend some time at water cooler conversations.

Don’t get me wrong, processes are definitely needed, but only if they serve a real purpose. This goes back to “control is OK as long as the controlled understand why and accept it”. Even the most draconian process will not erode trust if there is a sound reason behind and it’s well understood by everyone.

Arbitrary goals

This is the practice of setting goals and deadlines which have no backing in reality in hope to control how much people work. The implicit message here is also questioning the trustee’s motivation. Management often uses its power to avoid explaining why these goals are important in hope that the employees would have blind trust.

This can be a tricky practice to avoid since it requires full transparency all the way to the top. But this too is a topic for another blog post.

There are certainly a lot more control practices that erode trust, but I don’t want to end up writing a book so I’ll stop here. In a future post I will try to describe what companies can actually do to foster trust and reap it’s benefits.